Dr. Michael Heise on Global Economics

February 2020

In recent years, major central banks have been doing what they could to stimulate business activity and inflation. But the results have been meager, growth and inflation have remained sluggish. Correspondingly, the focus is now shifting to fiscal policy. With low interest rates in the US and even negative rates in Japan and the EMU, governments should be borrowing and spending more to get the economy moving and to reach societal goals. Calls for more spending can be heard in the US and in the EMU, especially with respect to Germany and other surplus countries. International organizations like the IMF and the OECD and the central banks themselves are shifting their focus to fiscal policies. Also the new EU Commission is proposing higher spending for a green deal, financed by bonds that the ECB would be capable of buying.

Such ideas have been supported by proponents of a „Modern Monetary Theory“. They claim that the governments that borrow in their own currency should be spending more to reach ambitious goals regarding education and equality, infrastructure or a green economy. Higher financial deficits of the government imply a bigger surplus for the private sector and therefore they are self financing in a sense. This group of economists denies the relevance of a classical budget constraint for the government as it can basically print the money it needs. The constraint for government activity is rather a possible inflation risk that would undermine positive effects of higher spending activity. In academic circles this is an outlyer view, as it seems to suggest the existence of a free lunch. But with policy makers the view has attracted some attention and the promise that important policy goals can simultaneously be reached through government spending does seem enticing. Unfortunately, there are a few errors and omissions in this line of thinking.

For one, the ability of governments to self-finance their spending activities with the help of their central bank presupposes that heavier spending and a larger money supply will not create inflation and reduce the credibility of the currency. Proponents of „integrated fiscal and monetary policies“ are less concerned bout this risk. They point to Japan where public debt in relation to GDP has risen to 240 % without any signs of a confidence crisis regarding the yen. But it is questionable whether Japan can really serve as a good example. Japanese government bonds are mainly held domestically by savers directly or by semi-public institutions that invest the savings oft he public. That is not true for US treasuries, half of which are held in foreign portfolios. Moreover, it is hard to see Japan as a model of success, as the surge of public debt has not achieved any significant long term economic growth.

Proponents of big public spending plans do not see major inflationary risks in the present economic environment. They point to the fact that years of Quantitative Easing (QE) and rising money supply have not generated inflation. And should inflation rise, tax increases would be possible to curb demand growth. Is that so easy? Probably not, as it would be politically very hard to put additional pressure on consumers just at a time when they see their purchasing power being eroded by inflation. Moreover, uncertainty about future tax policy will most certainly dampen investment and consumption plans of firms and consumers.

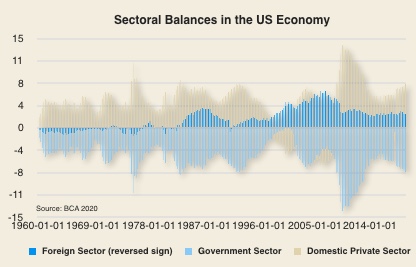

Further restrictions for central bank financed government spending can arise from the external balance of a country. Look at the US. Here the expansionary fiscal policy of recent years has increased the current account deficit, presently at around 500 bn USD, despite the repatriation of corporate profits that the tax reform incentivized. The financing deficit of the public sector is bigger than the positive balance of the private sector (chart). This has the inevitable result that foreign countries have a surplus with respect to the USA. Should the US government continue to expand its deficit, this will most likely be reflected by an even larger current account deficit and add to the already high net foreign debt of the US. Over time this would put downward pressure on the USD and reduce the real income of wage earners.

In other countries with sizeable external surpluses, as for example Japan and Germany, such concerns about foreign debt seem less relevant. But in the member countries of the currency union, direct financing of government activity via national central banks is prohibited by European treaties and national law. There is no unity of government and the Central bank in the currency union. And presently there is no political will in the member countries to centralize fiscal policy in any way. But even assuming – as a thought experiment – that there were still national central banks and national currencies, the scope for monetary financing of government activities would seem to be quite limited. Any doubts concerning the sustainability of public finances and the credibility of central banks would make risk premia on the countries debt soar thereby countervailing all positive effects of rising government spending.

The basic justification for deficit rules and budget restrictions is the political economy of short election cycles and strong incentives for policy makers to gain voter consent by additional spending. Especially if such spending is focused on transfers and consumption, future generations will inherit a high debt load without the real benefit of higher growth. Therefore, it is essential that the right fiscal choices are made and that public debt is used to finance investments conducive to long term growth.

Far-reaching proposals for government spending and the explicit use of central bank finance are based on political idealism. If policy makers are self-disciplined and do not misuse the instruments of central bank finance, if they are focused on the long-run performance of their economies and not on the next election, then the abolishment of budget constraints for the government may be benefitial. But unfortunately, this does not resemble our political reality.

Despite the fact that debt financed and central bank financed fiscal spending programs have negative repercussions in different ways, the policy incentives to embark on such a path are large. Therefore, for the next two to three years, we should expect a policy mix with somewhat stronger fiscal stimulus and ongoing monetary expansion that will keep the economic expansion alive. Combined with relatively low interest rates, this will continue to favor risk assets. Shocks like the Coronavirus or political risks in trade policies or Brexit issues may cause setbacks, but not a bear market as in a serious recession. Volatility should create buying opportunities.

Sie können hier Ihre Zugangsdaten beantragen. Diese werden Ihnen in Kürze per Mail zugeschickt.

[contact-form-7 id=“238″ title=“Contact form 1″]

+49 69 949488 050